Robert Alan Pentelovitch

Entretiens avec Alain Mercier

A.M. L’objet technique occupe une place essentielle dans votre œuvre. À quoi tient ce choix ?

Technical items take up an essential room in your work. What is the reason of this choice ?

R. P.

Technology surrounds us and is the driving force in our economy, therefore our submersion in this technological world has been somewhat taken for granted by the masses, and has developed a life of its own over the centuries. Due to the constant advancement and exponential growth of technological dependence we have generations of humans who have accepted machines as a natural element in their lives. My work explores our relationship with these machines on a cerebral level by accepting the inner beauty of this coexistence normally overlooked on the surface. The internal workings of these devices are fascinating to me and I depict them as architectural spaces wherein one cerebrally travels when considering the mechanism. To me the machines are many faceted artworks that I celebrate in my paintings, and they become an invitation to the viewer to share my deep appreciation of them.

A. M. Comment vous situez-vous par rapport à l’hyperréalisme ?

How are your situated compared with hyperrealism ?

R. P.

Traditional categories don’t apply to my work, though the Precisionist movement of the 1930’s surely has had an impact on my surface treatment. Hyperrealism tends to imitate photography very closely by fixating on depiction of reflection, surface replication, and shadow play. My work remains quite void of these trappings and is very abstract in depiction, surface representation, and particularly color usage.

A. M. Et par rapport à la photographie ?

And compared with photography ?

R. P.

Of course photography is an important tool for me as source material, and for documentation, but for the same reasons that my work differs from hyperrealism it too has little to do with a photo in terms of final product. Compositionally however my work often owes much to the medium and this may also be said of many hyperrealist works.

A. M. En découvrant vos tableaux, on comprend immédiatement qu’ils ne sont ni des plans, ni des études comparables aux lavis d’ingénieurs. Comment parvenez-vous à guider d’emblée le spectateur vers cette distinction ?

When discovering your paintings, one immediately understands that they are neither plans, nor technical studies like wash-drawings of engineers. How do you succeed in leading at the first go the spectator towards this distinction ?

R. P.

As an artist I create a product that is clearly a painting wherein I exploit the possibilities of the materials used within the context of subject matter that interests me. Though my interests are shared by technicians, engineers, inventors, and architects, my vision is clearly that of a fine artist. My painting vocabulary has developed a unique style that allows clear communication of my exaltation of machines. This tradition dates back to Leonardo DaVinci to whom painting was one of many idioms he mastered.

A. M. Vous jouez souvent, très habilement, sur une lègère déformation des perspectives (dans un tableau comme Carrier, par exemple). Pourquoi cet artifice ?

You often play, very skillfully, on a light deformation of perspective (in a picture like Carrier, for instance). Why such an artifice ?

R. P.

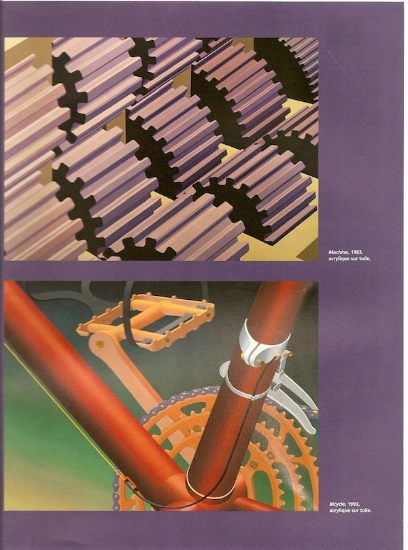

The spatial depictions are often motivated by my minds eye. In the case of “CARRIER” I worked directly from a dismantled gearbox, focusing on the differential as it lay in my studio, and allowing my mind to travel within the exposed spaces. I also restore automobiles as a hobby pondering the various components of these complex structures in cerebral contemplation, and I am attempting to communicate this dreamlike vision through my paintings. Though the painting is executed in grayscale there is subtle color introduced throughout.

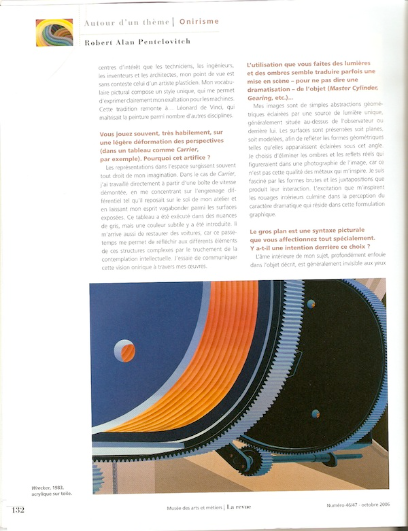

A. M. L’utilisation que vous faites des lumières et des ombres semble traduire parfois une mise en scène – pour ne pas dire une dramatisation – de l’objet (Master Cylinder, Gearing, etc.)...

Sometimes, your utilization of lights and shadows seems to translate a staging - not to say a dramatization - of the item (Master Cylinder, Gearing, and so on)...

R. P.

My images are simple geometric abstractions presented with a single light source generally located above and behind the viewer. Surfaces are presented as either flat or modeled to reflect geometric shapes as they appear lit from this angle. I choose to eliminate actual shadow and reflection that would appear in a photograph of the image because I am not interested in that quality of the metals that inspire me. It is the raw shapes and juxtapositions created by their interaction that fascinates me. The excitement of the inner workings culminates in the perceived drama presented by this form of presentation.

A. M. Le gros-plan est une syntaxe picturale que vous affectionnez tout spécialement. Y a-t-il une intention derrière ce choix ?

The close-up is a favourite syntax, for you. Is there an intention behind this choice ?

R. P.

The inner soul of my subject matter is generally hidden from the everyday user deep within the object depicted. Exposing the innermost workings of the depicted machine allows the viewer to step inside these hidden areas and harmonize with the interactions therein. Though the image may be derived from an intimate view they are presented on a grand scale to enhance the viewer’s perception of this otherwise overlooked environment.

A. M. Dans vos œuvres à sujet technique, deux thèmes sont récurrents : la mécanique et l’électronique. Pouvez-vous expliciter ce choix.

In your technical paintings, two themes are recurrent : mechanic and electronic. Would you explain this choice.

R. P.

I am primarily representing pure mechanics but I have also explored the world of electronic equipment. Now that circuit boards have become prevalent there is less interesting material for exploration in my opinion. There is a series of work that celebrates the colorful wiring harnesses used in various machines. These paintings are pure abstractions that were fun to execute, and present a visually attractive journey for the viewer, similar to an amusement park ride. It is the meshing of gears or the interesting negative spaces within a cross-section of a machine that truly interest me.

Lately I have been painting flowers and landscapes that evoke a very different emotion yet “DAHLIAS” is the culmination of my machine vision in the form of flowers. The petals become the cogs of gears, and the forms of the petals are presented in a metallic fashion, repeating mathematically as in a machine.

A. M. L’homme ne figure jamais dans vos tableaux. En est-il réellement absent?

Man never appaears in your pictures. Is he really absent of them ?

R. P.

The viewer is the human element. Including a figure would dictate scale, so I allow the viewer to enter the work intellectually creating their own perceived scale.

A. M. Le matériau (métallique notamment) a-t-il un impact sur votre sensibilité d’artiste ?

Does the material (notably metallic) have an impact on your artistic sensibility ?

R. P.

As stated earlier I rarely mimic metallic surfaces in a photorealistic fashion but rather model the image abstractly. There is nothing as tantalizing as painting red metal so I do admit to often choosing a red metal subject to work from. The viewer may assume that the images are representing metal objects based on their own preconceived notions. When the viewer enters the pictorial space with an open mind they will perhaps perceive concrete architectural depictions in machine forms or plastic materials depicted by virtue of the acrylic paint used in the production process.

A. M. Admettez-vous l’idée que vos sujets les plus « matériels » puissent inspirer au spectateur un climat onirique ?

Do you admeet the idea that your most « material » subjects may inspire to spectators an oniric atmosphere ?

R. P.

Yes that is my intention. The surrealist painters evoked a dreamscape through obvious tricks, but I am subtly suggesting that we interact with theses machines in a subconscious state. We somehow become one with the machines through our interdependence.

A. M. Situez-vous vos sujets dans une logique temporelle (celle de l’invention, par exemple) ou préfèreriez-vous qu’ils soient perçus en dehors de toute historicité.

Do you place your subjects in a temporal logic (the one of invention, for instance), or would you prefer them to be perceived out of any historicity ?

R. P.

This series of work simply celebrates the machine. These are real time depictions that are steeped in history while offering a window into the future. The timeline of a 19th century grist mill as depicted in “GRINDER” melds seamlessly with “LINKAGE”, a modern automobile transmission, or “HIGHWAY” that could foresee a future unknown. Though the series ended approximately ten years ago, their success is that they are timeless, having developed lives of their own.

A. M. Vos peintures ont suscité de nombreux expositions aux États-Unis. Peu ou pas en Europe. Pensez-vous le public européen moins réceptif que le public américain aux « sujets industriels » ?

Your work provoked many exhibitions in the United States. None or not a lot in Europe. Do you think that the european public is less receptive than the american one to the « industrial themes » ?

R. P.

No, Europe just has not discovered my work yet, and I am not much of a promoter. Many wonderful “Machine Works” have emanated from Europe and I am hopeful that mine will someday be shown amongst them. Admittedly I enjoy producing Art, though I equally dislike the “business” of art, so I am remiss in putting much effort into gaining exposure for my work. The fellowship bestowed on me by The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation in 1991 was an honor that provided the greatest achievement of my career to date and validated my work in a very respectable manner. Much of my work has been sold to collectors yet I do not measure success based on sales as much as academically so inclusion in this publication is of great importance to me and I am truly grateful for the honor and opportunity to share my thoughts herein.

A. M. L’art peut-il contribuer, selon vous, à familiariser le public avec la culture scientifique et technique ?

May the art contribute, in your own opinion, to familiarize spectators with the scientifical and technical culture ?

R. P.

My intention is to share my experience within these universes with the viewer by providing a thought portal. Art stimulates the imagination and the artist produces the scene to direct the viewer’s perception. Sometimes children perceive the true intent of my paintings quicker and more deeply than adults. One autistic boy was particularly fluent in his interpretations so perhaps I offered him a comfortable entrance into my world of “MACHINE WORKS”.

A. M. Une bicyclette ou un moteur ont-ils à vos yeux leur beauté propre, indépendamment même du parti qu’en peut tirer l’artiste ?

For you, do a bicycle or an engine have their own beauty, independently of the artist’s interpretation of them ?

R. P.

Absolutely! An automobile is the greatest rolling sculpture imaginable. My devotion to automobiles is only surpassed by my love of bicycles. This passion and enthusiasm derives from both the inner and outer beauty of the machines.

A. M. Pour quel peintre avez-vous le plus d’admiration ? Et pourquoi ?

Who is your favourite painter ? And why ?

R. P.

There is no single artist worthy of that distinction so I’ll name a variety: Michaelangelo, Leonardo Da Vinci, Pablo Picasso, Rembrandt, Vincent Van Gogh, Andy Warhol, James Rosenquist, Charles Sheeler, Red Grooms, Jim Dine, Georgia O’Keefe, and everyone who can draw and paint naturally as that is a gift so few actually possess.

A. M. Quel fut le premier musée à reconnaître votre talent ?

What was the first museum to recognize your talent ?

R. P.

My work is only represented in small ways in a number of American Museums so I await a major show one day to celebrate your question. Notably the Walker Art Center in my hometown of Minneapolis, Minnesota and the Anchorage Museum of Art in Anchorage, Alaska both have shown my work and the latter has a significant piece in their permanent collection.

A. M. S’il vous fallait désigner un endroit où exposer la toile de vous que vous préférez, choisiriez-vous votre maison ; le salon d’un amateur inconditionnel ; un hall de gare ; un musée ; un tout autre lieu ?

If you would have to choose a place where to exhibit the painting of yours that you prefer, would it be home ; an unconditional fan’s home ; a station hall ; a museum ; another place ?

R. P.

The environment I prefer is full of my creations as they represent my personal visual vocabulary. Ultimately the work on my easel currently is the one that interests me most and the past works become reference points in my creative process.

Ideally a museum show is the best exhibition space for my paintings, giving them maximum exposure in an ideal atmosphere for the viewer’s enjoyment as well as providing a stable climate controlled environment to preserve them for future generations.

Fortunately my work is accessible to everyone through my website: www.pentelovitch.com and I welcome everyone to visit often and stay as long as possible.

Thank you for your well thought out questions, your interest in my work, and for sharing my thoughts with your readers.